Slovakia faces rising expenditures due to adverse demographic developments, adding pressure to public finances[1], which are already showing exceptionally high deficits. Preparing reports on the long-term sustainability of public finances is one of the core responsibilities of the Council for Budget Responsibility (CBR), as defined by the constitutional Fiscal Responsibility Act[2]. These sustainability reports assess whether the current public policy framework is fiscally sustainable in the long term, based on projected demographic and macroeconomic developments.

Long-term sustainability of public finances in 2024 is in the medium-risk zone

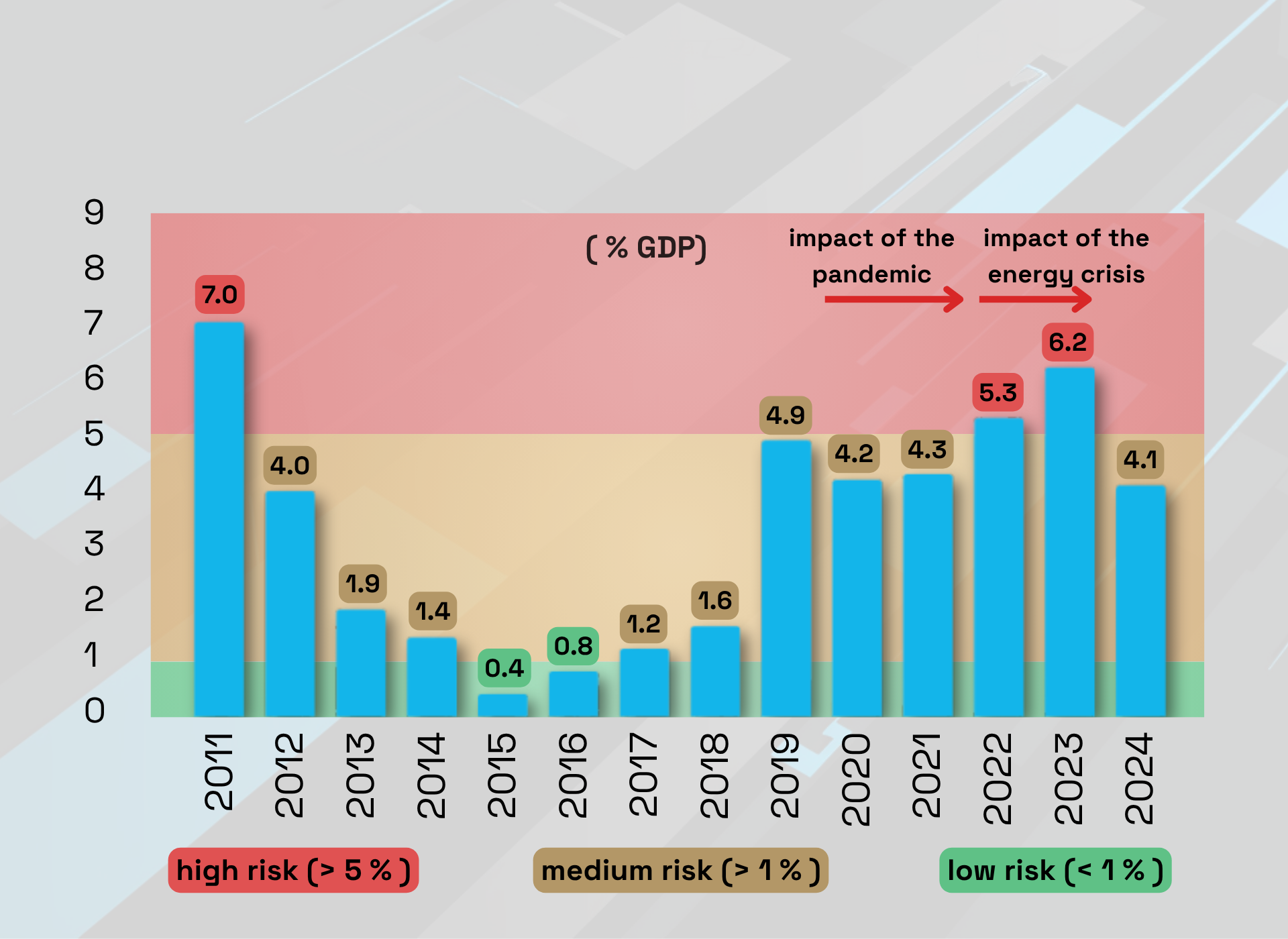

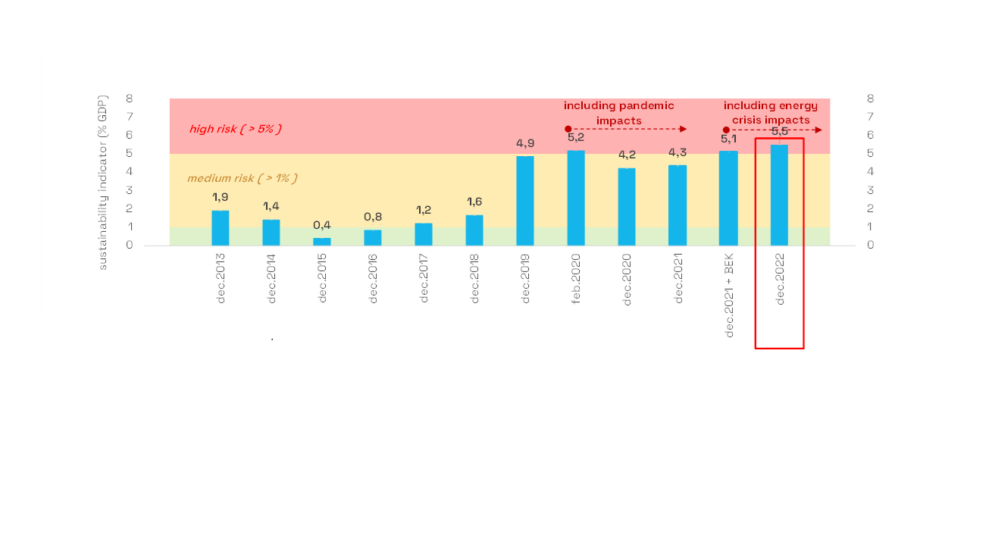

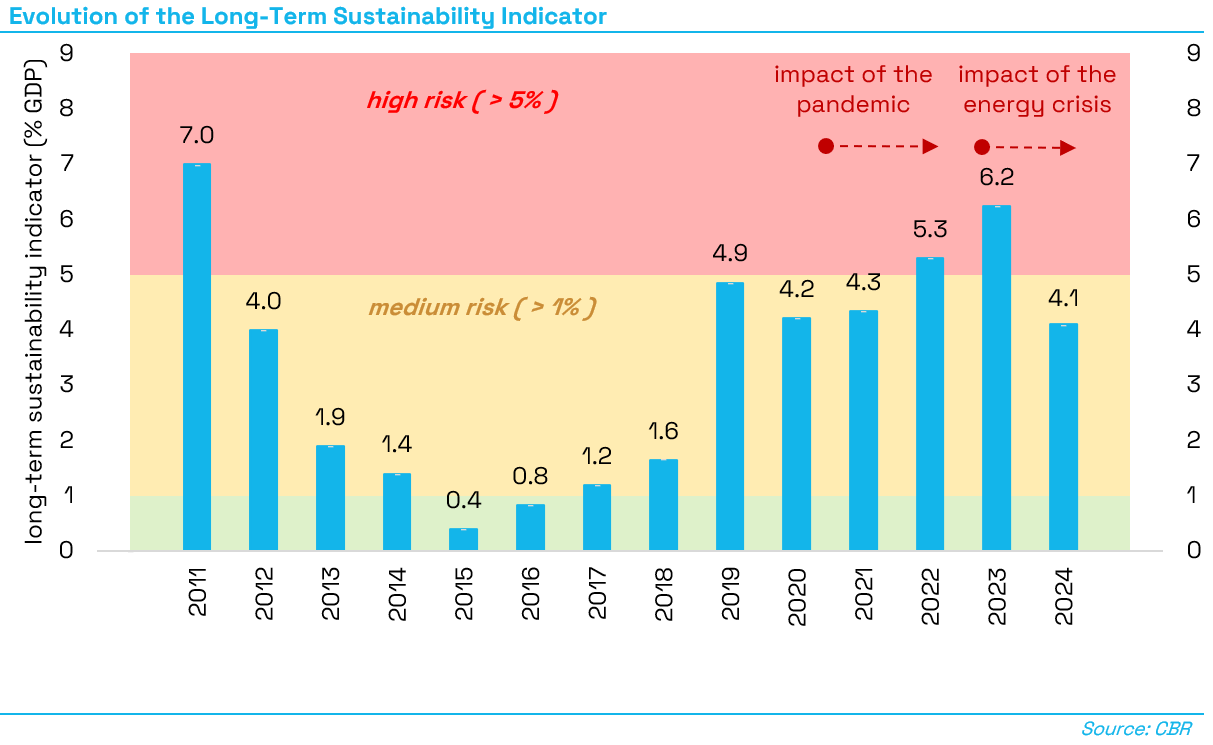

The baseline scenario in this report reflects Slovakia’s fiscal position at the end of 2024, incorporating the impact of measures adopted throughout the year. The long-term sustainability indicator reached 4.1 percent of GDP (EUR 5.7 billion), corresponding to the medium-risk zone[3]. This means that long-term sustainability was not achieved[4] in 2024 and that the fiscal burden continues to be shifted onto future generations.

Compared to 2023, there has been visible progress, driven by several measures adopted by the government and parliament. After two years, long-term sustainability has returned to the medium-risk level observed in 2020 and 2021, a period marked by the COVID-19 pandemic and occurring before the security-energy crisis. This level is even lower than in 2019, prior to the pandemic. However, the current structural deficit is significantly higher than during these earlier periods, underscoring the need for a sustained and ambitious fiscal consolidation effort. Without additional measures, public debt is projected to rise sharply over the medium term. By the end of 2024, gross debt reached 59.3 percent of GDP, compared to 48.0 percent at the end of 2019, i.e. before the outbreak of the pandemic. The structural deficit has also worsened to 4.2 percent of GDP, nearly two percentage points above its pre-pandemic level of 2.3 percent. This deterioration reflects a surge in expenditure funded from savings anticipated in the future. As a result, the debt growth rate is expected to accelerate in the coming years, which will reduce the fiscal space for future sustainability improvements through savings, particularly in the long term.

At the same time, a significant increase in the tax burden, the highest in the past 25 years, has reduced the scope for further consolidation through tax increases.

The high deficit of the pension system, which is expected to worsen further over time, accounts for more than half of the long-term sustainability gap.

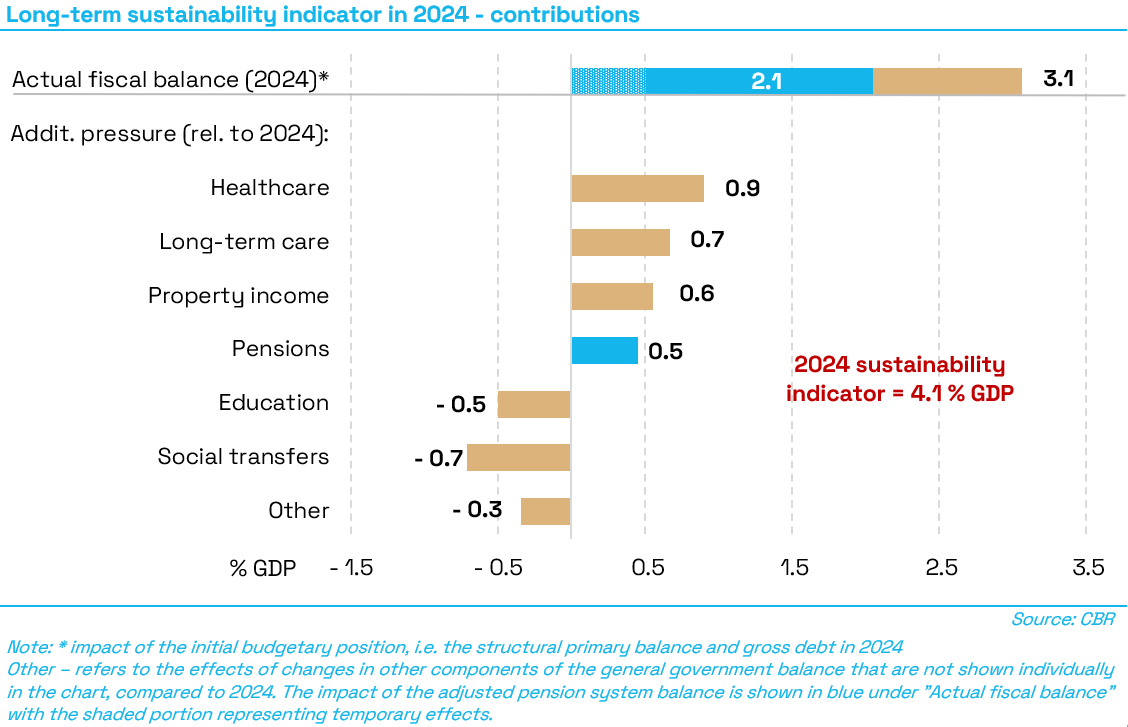

The current situation in public finances, with a high deficit in 2024 and a debt exceeding the upper limit defined by the constitutional act as the decisive factor for calculating the long-term sustainability, contributes negatively to the long-term sustainability of public finances by 3.1 p.p. The contribution of the pension system deficit[5] is negative, standing at 2.1 p.p.[6]

The expected increase in age-sensitive expenditure and other implicit liabilities is also playing its role in the negative long-term outlook for public finances, with its contribution totalling 1.4 p.p. CBR expects healthcare and long-term care expenditure to have the most significant additional negative impact compared to the current state of public finances. To a lesser extent, the pension system is another contributor to the worsened situation, especially given its exceptionally high level of expenditure[7] at present. On the other hand, the impact of the estimated decline in spending on social transfers and education is positive.

Other general government revenue and expenditure contribute slightly positively to the long-term sustainability (0.3 p.p.), in particular due to expected developments over the next five years. The consolidation of public finances at the end of 2024 with an impact from 2025 onwards is a major contributor to improving the development of public finances, but its medium-term effects are nearly fully offset, for the most part, by increased defence spending[8], other expenditure-increasing measures and by the expiry of temporary taxes and social contributions after 2027.

Consolidation measures adopted in 2024 had the strongest impact on improving long-term sustainability

Compared to 2023, the sustainability of public finances improved by 2.1 percent of GDP in 2024. The measures adopted during 2024 were the main driver of this improvement, contributing a total of 1.8 percentage points to the long-term sustainability indicator:

- Starting in 2025, the approval of the so-called consolidation package contributes 1.3 percent of GDP to the improvement of the sustainability indicator. The package includes, in particular, changes to VAT, the introduction of a financial transaction tax, and adjustments to income tax. This impact also reflects pension-related measures, notably a substantial reduction in the parental pension and an increase in the maximum assessment base for social insurance contributions.

- Other revenue-increasing measures, which were approved before the adoption of the consolidation package (introduction of excise duty on sweetened non-alcoholic beverages and an increased excise duty on tobacco products), improve the indicator by 0.2 percent of GDP.

- In addition to the two measures mentioned above, two further legislative changes were adopted in relation to the pension system. One measure with an immediate impact is the increase in the 13th pension, which worsens the sustainability indicator by 0.4 percent of GDP. Conversely, the introduction of stricter eligibility criteria for early retirement improves the indicator by 0.4 percent of GDP. However, the positive effects of this measure will materialise gradually over the long term. This will translate into a faster debt growth rate over the next ten years.

- Slower wage indexation in the public sector in 2025 and 2026[9] contributed to an improvement in the sustainability indicator by 0.4 percent of GDP. However, this improvement is conditional on adherence to collective agreements and the assumption that public sector wages will not grow significantly faster than wages in the private sector. Other measures approved during 2024 contribute to the deterioration of the indicator by 0.1 percent of GDP.

New European fiscal rules have also contributed to the adoption of consolidation measures in 2024, but they might not be strict enough in the years ahead

Applicable from April 2024, the reformed European fiscal rules served as the basis for Slovakia and the EU Council in approving the maximum rate of net expenditure growth until 2028[10]. Consolidation measures adopted in 2024 might help comply with the rule in 2025[11]. However, there is a risk that, in the coming years, these rules will not lead to a substantial improvement in Slovakia’s public finances and long-term sustainability:

- For Slovakia, setting the net expenditure growth rate remains largely discretionary. According to the CBR, compliance with the prescribed expenditure path would not lead to a sustainable reduction of the deficit below 3 percent of GDP and the debt below 60 percent of GDP, which runs counter to the primary objectives of the new fiscal rules[12].

- In March 2025[13], in response to the geopolitical situation and the need to increase defence spending, the European Commission enabled the activation of a national escape clause for the next four years. This clause allows increased defence spending[14] to be considered when assessing compliance with the net expenditure rule.

Fiscal burden shifted to future generations

As indicated by generational accounts, the fiscal burden is being transferred to future generations. Individuals born in 2024 are expected to receive, over their lifetime, approximately EUR 96,000 more from public budgets than they will contribute. However, if current public policies remain unchanged, future generations will face the opposite situation. They would pay around EUR 71,000 more than they would receive, assuming they bear the full cost of current liabilities, including existing public debt, which alone accounts for EUR 32,000 of that burden.