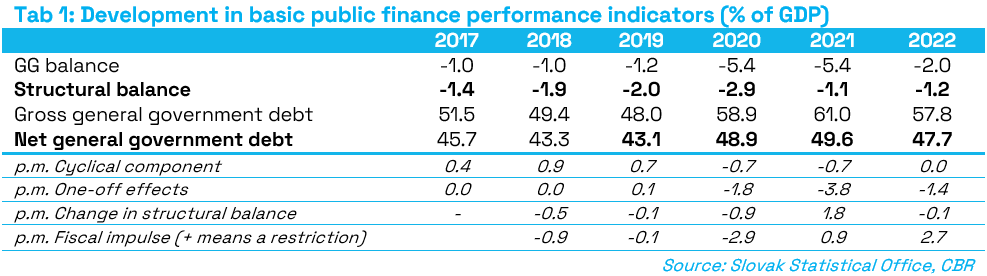

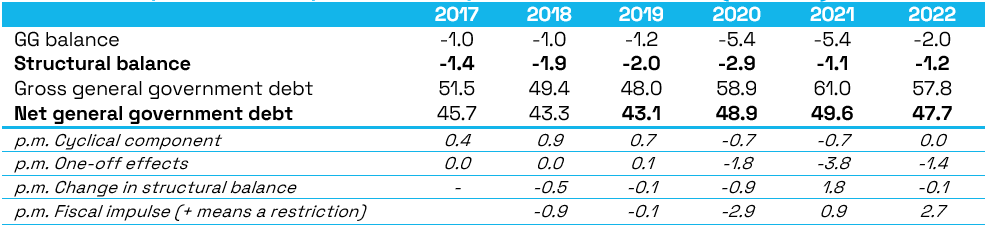

The deficit of the general government (GG)[1] amounted to 2.0% of GDP in 2022, a considerably better result against the target approved in the 2022 budget at 4.9% of GDP[2]. The positive difference of as much as 2.9% of GDP from the target deficit represents the largest improvement since 2005[3]. The gross debt stood at 57.8% of GDP, 3.7% of GDP less than expected in the budget.[4]

Tab 1: Development in basic public finance performance indicators (% of GDP)

Source: Slovak Statistical Office, CBR

Source: Slovak Statistical Office, CBR

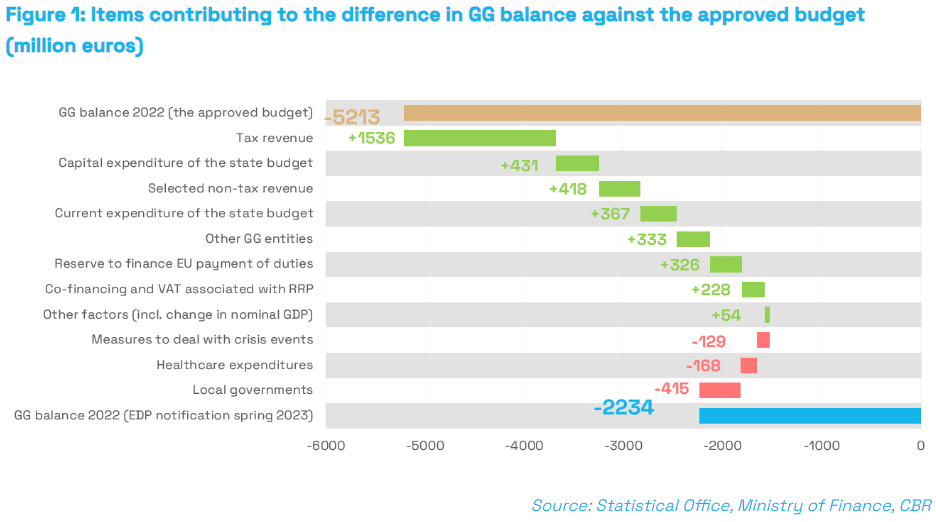

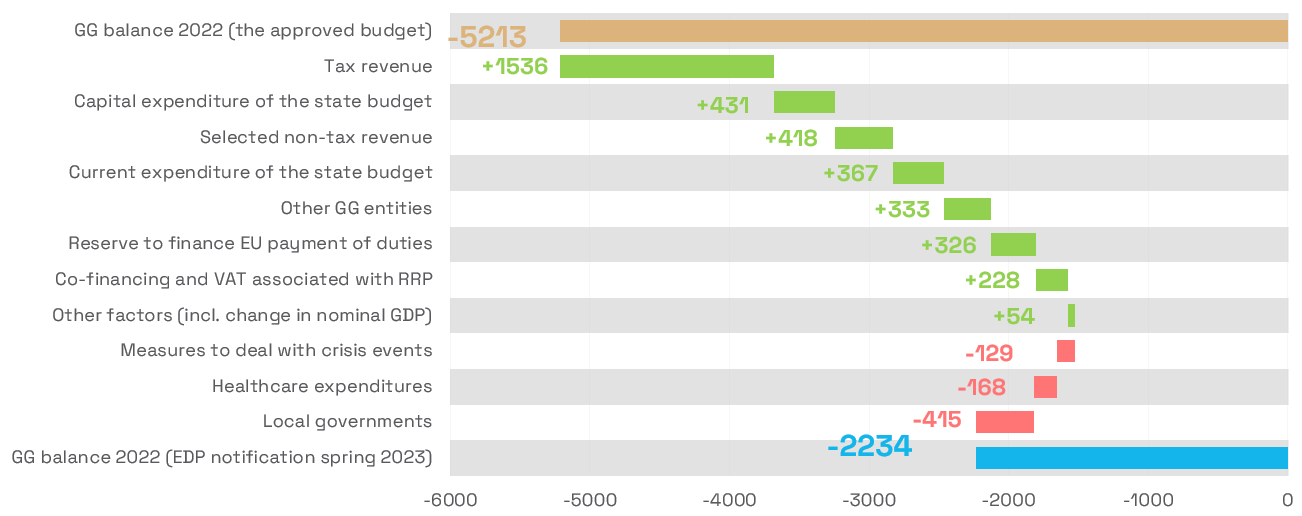

The largest deviations in the general government fiscal performance in 2022 from the budgetary projections were directly associated with a high growth in prices, as well as other consequences of the war in Ukraine. On the positive side, tax and contribution revenues rose by 1.5bn euros (1.4% of GDP), mainly driven by a higher-than-expected growth in nominal macroeconomic indicators increasing the gains from taxes. On the other hand, negative impacts on the general government deficit included increased spending on temporary measures in connection with the war and with compensations of the high growth in prices, as well as on measures to address the pandemic in excess of the budgeted reserve whose total contribution to the increase in the deficit amounted to 129mn euros (0.1% of GDP).

- The significant increase in tax revenues was mainly driven by a faster growth of nominal values due to a considerably higher-than-expected inflation. Higher macroeconomic bases affecting the tax revenues contributed additional revenues in a total amount of 6bn euros (1.5% of GDP) above the budgetary target. New measures and/or improved tax collection contributed further 0.3bn euros.

- There were also other major factors, not directly related to the crisis produced by the war and/or the pandemic, that contributed to the deviation in the final fiscal results from the budgetary target. The slower capital spending from the state budget brought in savings of 413mn euros (0.4% of GDP), especially due to postponed deliveries of military equipment in the defence sector. Non-tax revenues were 418mn euros (0.4% of GDP) higher. As far as the EU budget funds are concerned, the reserve for customs duty payments of 326mn euros (0.3% of GDP) was not used, while the slower-than-expected uptake of EU funds and the Recovery and Resilience Plan funding saved 228mn euros (0.2% of GDP) on co-financing. 505mn euros (0.5% of GDP) had been earmarked in the budget to cover expenditures on economic measures and supporting the economy (the so-called economic reserve), the use of which had been contingent on the approval of three constitutional reforms which, however, were not signed into constitutional law[5]. Nevertheless, the reserve was used to cover additional expenditures in other budgetary areas.

Figure 1: Items contributing to the difference in GG balance against the approved budget (million euros)

Source: Statistical Office, Ministry of Finance, CBR

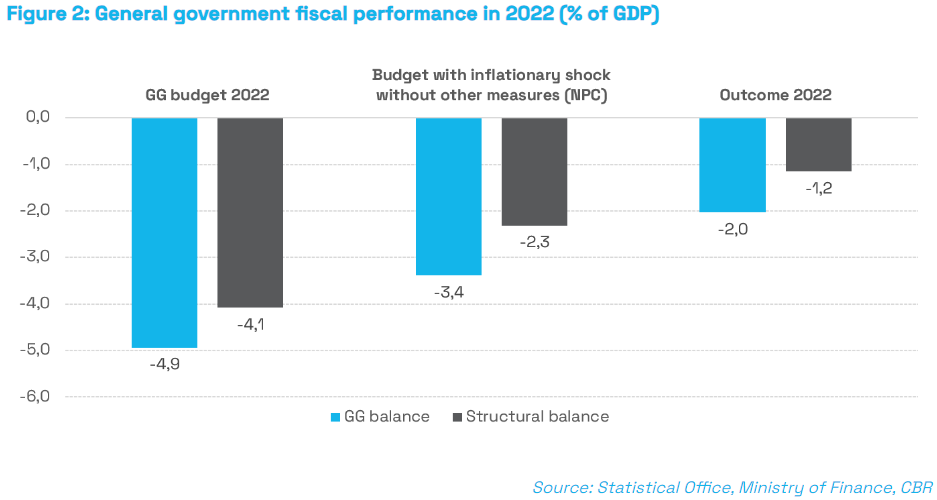

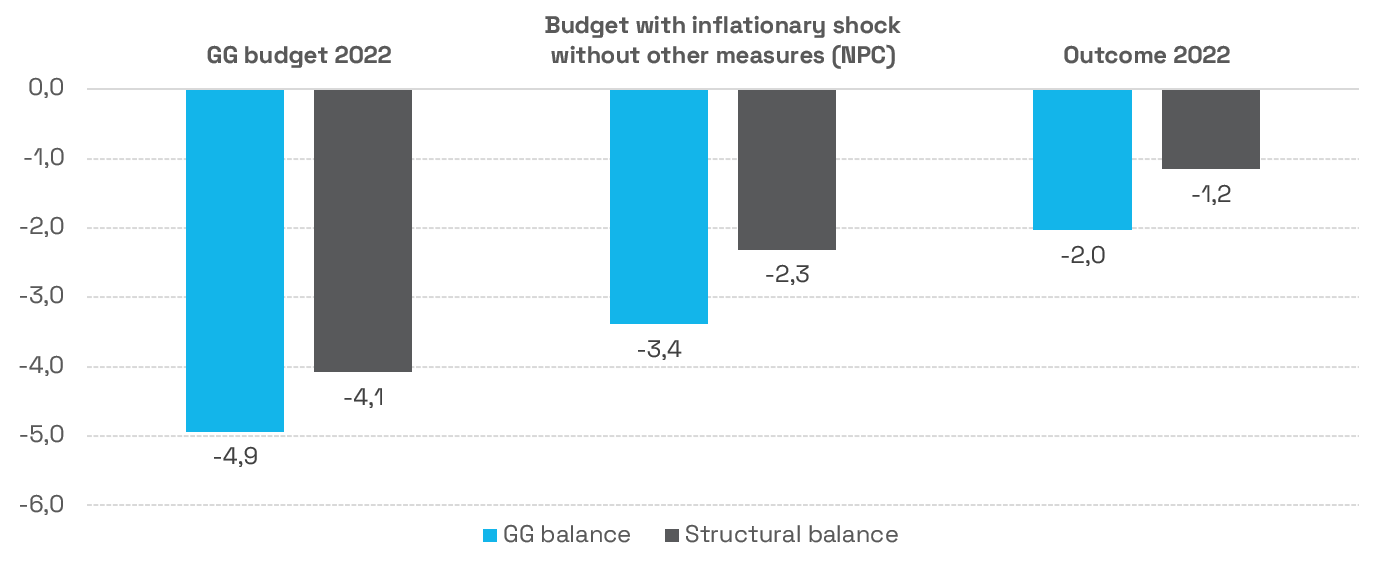

The major deviations from the budgetary targets were directly associated with the high growth in prices. On the positive side, tax and contribution revenues increased, on the other hand, the inflation has a negative impact on expenditures which, however, will fully show with a year-long delay. If no measures were adopted, the impact of the inflation shock would improve the deficit to 3.4% of GDP. Also owing to a Commission regulation, the government to a large degree covered extraordinary expenditures by new, extraordinary revenues to ease the impact on the debt. The remaining expenditures rose at a slower-than-expected pace. Savings in current expenditures of the state budget occurred despite the considerably higher inflation. By contrast, local government expenditures rose during their election year, and health expenditures were higher than budgeted, as well. Customs duty payments on Chinese imports were recorded in the deficit in 2021 instead of 2022.

Figure 2: General government fiscal performance in 2022 (% of GDP)

Source: Statistical Office, Ministry of Finance, CBR

From the point of view of a medium-term burden on public finances, it is better to focus on the structural deficit indicator (i.e., a deficit that will automatically last even into the future, if no additional measures are adopted[6]). The 2022 structural deficit remained unchanged year-on-year at the level of 1.2% of GDP, its ever lowest level, along with the 2021 structural deficit. However, the low level of structural deficit in 2022 is partially driven by a delayed increase in public spending in response to inflation growth, which will occur, especially in the area of social transfers and wages, in 2023 and 2024. For this reason, the 2022 structural balance may not give a full picture of public finances in the medium term.

The gross debt stood at 57.8% of GDP, down 3.2 p.p. year-on-year, which means, however, that the debt still remains above the highest debt-brake sanction bracket that starts at 55% of GDP. The decline in gross debt was mainly driven by high inflation, reducing the debt to GDP ratio by as much as 4.2 p.p., while the real economic growth helped to decrease the debt by 0.9 p.p. An effect in the opposite direction came from the general government primary deficit and the public debt interest payments, each increasing the debt by 1.0 p.p. Interest rates increased in 2022, which will only gradually reflect in higher interest payments depending on the debt maturity. Topping up the reserve at the time of low interest rates and an uncertain access to financial markets lead to savings in future interest payments. Statistically, however, the reserve increases the gross debt rate[7].

Fiscal policy (coupled with EU funding and one-off expenditures) supplied a notable restrictive impulse of 2.7% of GDP in 2022. The strong fiscal restriction mainly results from a year-on-year decrease in spending on pandemic-related measures (down 2.4 p.p. of GDP year-on-year), which was only partially erased by new measures to compensate high prices and respond to the war in Ukraine. Temporary measures are best suited to respond to this type of crisis because once the crisis is over, these measures expire as well and will not burden public finances over the long term. Net of the effect of the pandemic-related measures, the fiscal impulse was more or less neutral in 2022, corresponding to the approximately neutral cyclical position of the economy.

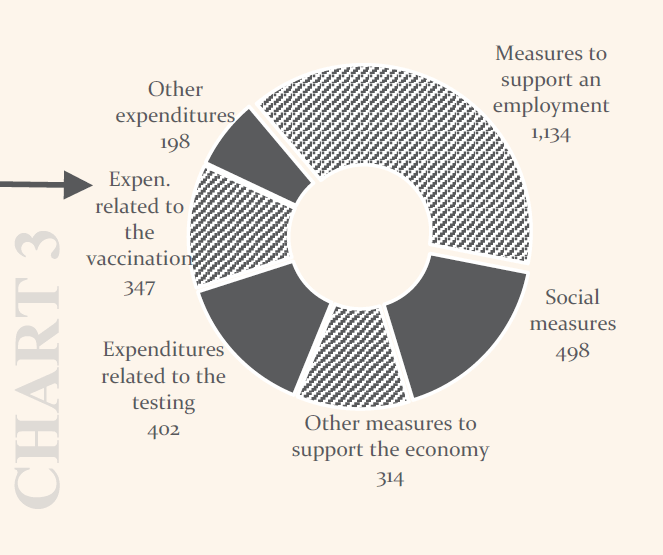

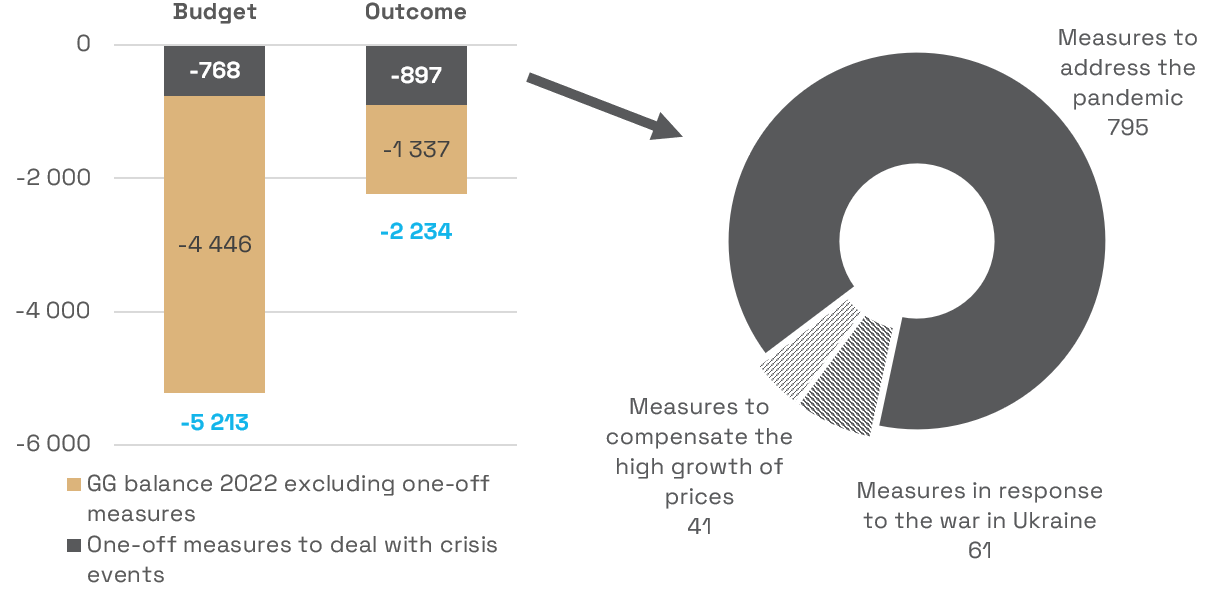

Also owing to a Commission regulation, the government to a large degree covered extraordinary expenditures by new, extraordinary revenues to ease the impact on the debt. The government responsibly used the extra room even beyond that provided under the Commission regulation. Total expenditures to finance the measures adopted by the government in response to exceptional circumstances, i.e., the pandemic, the war in Ukraine and the high growth in prices, amounted to 1.4bn euros (1.3% of GDP). After deducting the revenues from the solidarity contribution and grants received by the defence ministry in connection with the supply of military equipment to Ukraine, these measures increased the general government deficit by 897mn euros (0.8% of GDP), however, all of them were one-off measures with no effect on the structural deficit. On the other hand, the budget included a reserve in the total amount of 768mn euros to cover the negative impacts of the pandemic and the pandemic benefits in the budget of the Social Insurance Agency. Therefore, the temporary measures adopted by the government in response to exceptional circumstances increased the budget deficit by mere 126mn euros (0.1% of GDP).

Figure 3: Measures adopted to address crisis events increase deficit by 0.9bn euros

Source: Statistical Office, Ministry of Finance, CBR

- The measures adopted to address the pandemic, with the total budgetary impact of 795mn euros (0.7% of GDP), had the largest impact on the increase in the general government deficit. They mainly included the costs of covid testing and vaccination, including the costs of procuring medications and vaccines, expenditures on economic mobilisation and the purchase of medical materials. Other pandemic-related measures included the support schemes to retain employment (so-called kurzarbeit), as well as additional support in the form of measures to support the economy, such as rent refunds and support to travel industry companies.

- The measures adopted in response to the war in Ukraine cost a total of 194mn euros (0.2% of GDP). The expenditures spent on humanitarian aid, contributions for the accommodation of refugees from Ukraine and other additional costs were partially offset by the grants received by the defence ministry for the supply of military equipment to Ukraine. The net budgetary impact of these measures amounted to 61mn euros (0.06% of GDP).

- The costs of measures to compensate the high growth in prices totalled 452mn euros (0.4% of GDP). The government operated multiple schemes for one-off assistance to vulnerable groups of population, such as 14th pension payments or a one-off increase in child allowance. Funding was also provided for the schemes designed to compensate the increase in energy prices for undertakings. The additional expenditures were almost fully covered by 412mn euros (0.4% of GDP) in revenues from the solidarity contribution from the operations in selected economic sectors approved as a follow-up to the Council regulation. As a result, the measures to compensate high energy prices increased the general government deficit by 41mn euros (0.04% of GDP).

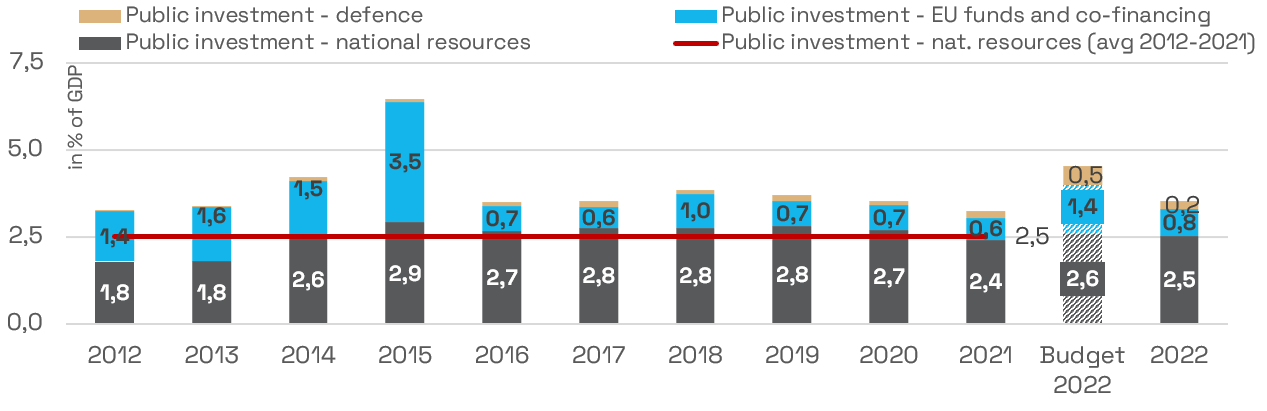

From the perspective of long-term sustainability, the long-term economic growth is important. It can be supported by the formation of new capital through effective public investments. Because the flow of European funds depends on a longer-term spending plan, the development of domestic public investments will be interesting to observe. At the same time, it is advisable to deduct the investments related to the military equipment, because the size of these expenditures recorded in the budget balance under ESA 2020 is to a large degree affected by delivery dates. In 2022, the uptake of domestic investments outside the defence sector showed a moderate year-on-year increase, mainly driven by local government, but, as in the previous year, remained slightly below the level of capital expenditures included in the budget. The investments were 0.1% of GDP less than expected in the budget; on the one hand, this contributed to the low level of structural deficit, on the other hand, the government failed to fully use the budgetary funds to support investments that are much needed for economic growth. The final size of domestic investments was at the level of historical average since the previous crisis.

Figure 4: Public investments increase year-on-year, fail to meet the pre-pandemic levels

Source: Statistical Office, Ministry of Finance, CBR

[1] For the purpose of assessing the development in public finances, the general government consists of the central government (state budget, organisations partly funded from the state budget, and other general government entities), the Social Insurance Agency and health insurance companies, and local government (municipalities and self-governing regions).

[2] In view of windfall tax revenues and the need to fund compensation measures, the State Budget Act was amended in October 2022 to increase the cash revenues and expenditures of the state budget with no effect on cash deficit. Along with this adjustment, the Ministry of Finance published a draft budget for 2023-2025 in which it estimated the general government deficit at 5.0% of GDP. This value, however, was not approved as a government’s new balance target. In light of the above considerations, the CBR assesses deviations from the original budget approved in December 2021 in this paper.

[3] The deficit was 1% of GDP lower against the most recent estimate published in March 2023 as part of the so-called budgetary traffic lights.

[4] Unless otherwise specified, this document has been produced using the input data from the Slovak Statistical Office, the Ministry of Finance, and the CBR’s calculations.

[5] The expenditure ceilings were enacted through a regular law, as well as the pension system reform (after the fixed retirement age ceiling, as a financially destabilising factor, had been removed from the Constitution). However, an amendment to the constitutional Fiscal Responsibility Act was not approved due to the requirement of implementing a tax brake, and the act in its current wording is thus not aligned with the expenditure ceiling rules.

[6] The structural balance does not include one-off and temporary measures that do not represent a burden on the development of public finance in the long term.

[7] At its average level for the 2005-2021 period, the gross debt would be at 55.0% of GDP.