Summary

The Report on Compliance with the Fiscal Responsibility and Fiscal Transparency Rules annually assesses the compliance with the rules arising from the constitutional Fiscal Responsibility Act[1] for the previous year, always by 31 August. In addition to evaluating the development of long-term sustainability of public finances – the most significant objective pursued by the act – it also assesses compliance with the constitutional debt limit, as well as other statutory obligations, especially regarding data reporting and publication, local government debt, and the funding of local government’s competences.

Long-term sustainability of public finances

The key objective of fiscal responsibility is to achieve sustainable public finances. The protection of long-term sustainability of Slovakia’s economic performance regarding the compliance with the principles of transparency and effectiveness of public spending was enshrined in an amendment to the Constitution of the Slovak Republic[2] in 2020.

The CBR has concluded in its evaluation[3] that the long-term sustainability of public finances was not achieved in 2023. The long-term sustainability indicator reached 6.2% of GDP under a no-policy-change scenario; this means that public finances are currently in the high-risk zone.

From the beginning of 2024 to the end of August 2024, multiple measures were either implemented, or are pending approval (adjustment of the parameters for early old-age pension payments, introduction of a tax on sweetened non-alcoholic beverages, increase in the excise tax on tobacco partially offset by the introduction of the 13th pension payments and new state budget expenditures), which have contributed to a slight improvement in the long-term sustainability indicator by approximately 0.1% of GDP compared to the estimated development at the end of 2023. These measures, however, are not sufficient to reduce the high risk associated with the development in public finances.

Considering the poor condition of public finances, affected by external factors outside the government’s control (the security and energy crisis) in addition to the implemented measures with a negative impact on the balance, the government should present sufficiently ambitious measures to improve long-term sustainability as soon as possible. In addition, the need to improve long-term sustainability is further augmented by the current high level of gross debt which has now been in the highest sanction bracket of the debt brake rules for four consecutive years.

Starting from 2023, effective implementation of the expenditure ceilings could have contributed to the improvement of long-term sustainability. However, this did not occur. The expenditure ceilings applicable to 2023 were not binding for the budgetary process due to an exemption applied in connection with the European rules of the Stability and Growth Pact [4]. The 2024-2026 budget was not prepared in accordance with the applicable expenditure ceilings[5] and a legislative amendment was subsequently approved in 2024 under which the public expenditure ceilings became linked to the European rules, thus ending the original rule directly linked with the definition of long-term sustainability of public finances included in the constitutional act.

The government failed to take advantage of the good macroeconomic developments, especially since the summer of 2023, for a gradual and permanent consolidation of public finances; the start of consolidation efforts is therefore not expected before 2025. Despite the consolidation package[6] approved at the end of 2023, long-term sustainability has been further deteriorating in 2023 and 2024 due to the effect of the measures taken by the government.

In accordance with the revised fiscal rules under the EU’s Stability and Growth Pact, the government must submit a national medium-term fiscal-structural plan[7] by 20 September 2024 which should present a fiscal strategy for a reliable reduction in general government debt and deficit, including priority investments and structural reforms. The Ministry of Finance has yet not published a reference path (trajectory) sent by the European Commission to Member States. According to independent calculations of the Bruegel institute, as well as according to the CBR’s estimates, the requirements for the consolidation of Slovakia’s public finances are expected to be among the most stringent of all EU countries. This is mainly caused by the unfavourable starting position of public finances, or the lack of consolidation efforts in 2023 and 2024, and the estimated increase in the costs related to ageing population. However, in order to improve long-term sustainability, the credibility and enforceability of the new rules, as well as a concrete structure of consolidation measures[8], will be crucial.

Fiscal responsibility rules

In order to achieve long-term sustainability of public finances, the expenditure ceilings and the upper limit on general government debt (the so-called debt brake) have been established by the constitutional act. Both these mechanisms were supposed to contribute to achieving long-term sustainability of public finances.

However, the way the constitutional act is currently applied by both the government(s) and the parliament[9] has failed to provide sufficient safeguards for long-term fiscal sustainability, in particular due to the absence of effective expenditure ceilings and a purely formal approach to compliance with the debt brake sanctions. Therefore, the constitutional act should be revised to reflect the current debt development, the need for effective liquidity management and, above all, to make the debt brake an effective instrument for improving the long-term sustainability (for example, by introducing stricter measures when lower sanction brackets are exceeded and by protecting the economy from an abrupt change in the fiscal policy while maintaining sufficient consolidation); this, however, requires reaching a consensus across party lines. A change in the governments’ and parliament’s approach to the fiscal responsibility rules is also a prerequisite for effectively safeguarding the long-term sustainability of public finances. A formal approach, which tends to circumvent the purpose of these rules, must be replaced by actual compliance. A mere tightening of the debt brake sanctions or refining the provisions of the constitutional act may not be enough if there is no functioning mechanism in place to enforce compliance with those provisions. Last but not least, it must be understood that effective fiscal rules, whether at national or European level, represent only the minimum standards for responsible fiscal management. The rules set reasonable minimum limits, but do not necessarily provide optimal guidance for fiscal policy if all of Slovakia’s needs are considered.

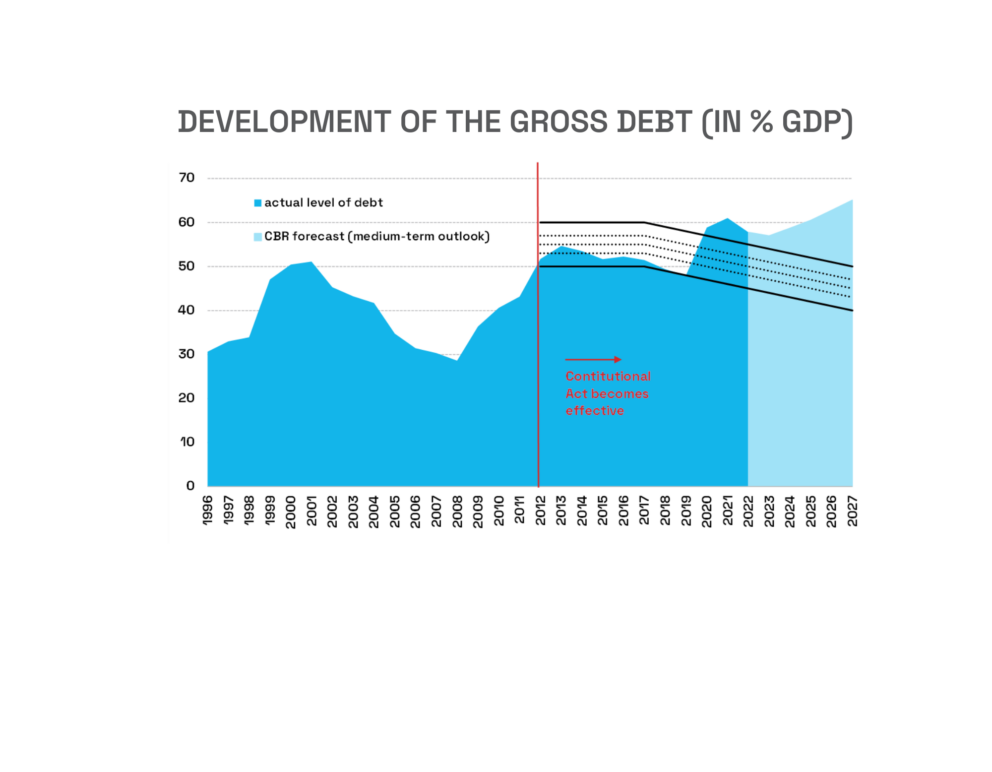

General government debt limit

The debt-to-GDP ratio reached the highest, fifth sanction bracket of the debt brake rules[10] in 2022 and 2023. According to the data published by Eurostat in October 2023, the debt stood at 57.8% of GDP at the end of 2022, while the preliminary data[11] released in April 2024 indicated that it reached 56.0% of GDP at the end of 2023.

Since the 24-month exemption from the application of more stringent sanctions under the constitutional act[12] did not apply between 5 May 2023 and 21 November 2023, the amount of the 2022 debt was subject to the sanctions triggered by the overrunning of the thresholds of all five sanction brackets under the constitutional Fiscal Responsibility Act during this period. The debt brake sanctions apply cumulatively, starting with the sanctions triggered by exceeding the second sanction bracket up to the highest one (Table 1).

Due to the application of the 24-month exemption, the size of debt achieved in 2023 has triggered sanctions resulting from exceeding the first two sanction brackets under the debt brake (Table 2).

Despite the high levels of general government debt, which has since 2020 remained continuously in the highest sanction bracket of the debt brake, the sanctions have repeatedly been complied with in a merely formal manner, having a minimal impact on the reduction of the general government debt:

- The government repeatedly submits a document to the parliament for discussion on the reasons for the size of the general government debt and a proposal for measures leading to its reduction. The CBR repeatedly warns that the document does not contain a sufficient list of specific measures to reduce the debt and fails in practice to meet the objective pursued by the sanctions, i.e., to reduce the general government debt below the sanction brackets. In fact, a document on the 2022 debt was not submitted at all, or more precisely, the government submitted a cumulative document for 2022 and 2023 in July 2024, which is not permitted under the constitutional act.

- The government blocked 3% of total state budget expenditures in May 2023; however, it did so for items that do not affect the general government balance. Again, this was only a formal compliance with the relevant provision of the constitutional act with no real impact on the reduction of the general government debt.

- The government had submitted a balanced budget proposal for 2024-2026 to the parliament, which was withdrawn after a temporary exemption from the application of the strictest sanctions of the debt brake was triggered. In the proposal, the government itself noted that the adoption and implementation of the balanced budget would cause a recession and jeopardise the functioning of the state, and explicitly stated that it saw the submission of the balanced budget proposal merely as the fulfilment of its legal obligation[15].

According to the authors of the constitutional Fiscal Responsibility Act, the implementation of the measures triggered by the overrunning of the debt-brake sanction brackets should lead to a reduction of the public debt to a safe level. However, the measures adopted by individual governments have long fallen short of this objective. Experience has shown that governments are unwilling to truly comply with the constitutional act and regularly circumvent the sanctions under the debt-brake mechanism. In doing so, they ignore the purpose of the legislation, which is to achieve a sustainable fiscal performance of the Slovak Republic.

The Slovak Republic, that is, all its government bodies and public authorities, should protect the long-term sustainability of the country’s economy. If the economy is not sustainable in the long term, the state may not be able to properly ensure the protection of fundamental rights in the future, especially those that depend on public funding[16]. When preparing a general government budget proposal and measures to safeguard the long-term sustainability of public finances, the government has discretion only within the limits set by generally binding laws and regulations[17]. A merely formal approach to the interpretation and implementation of relevant constitutional standards is inadmissible. Such formal compliance with the constitutional act, without fulfilling its purpose, may be considered as its violation[18].

According to the CBR’s medium-term estimate[19], the gross debt will increase cumulatively by 10.7 p.p., from 56% of GDP at the end of 2023 to 66.8% of GDP at the end of 2028, if no additional consolidation measures are taken. The estimated increase in the general government debt is mainly driven by an extremely unfavourable development in the structural primary balance. The highest sanction bracket of the debt break will start at the level of 50% of GDP in 2028, which means that it will be exceeded by 16.8 p.p. Taking into account the two-year exemption from the application of the strictest debt-brake sanctions following the approval of the government’s manifesto of the new cabinet formed after the early parliamentary elections in the autumn of 2023, there is a serious risk that a balanced budget proposal for 2026, with no increase in expenditure, will have to be submitted again.

Public expenditure ceilings

In addition to the debt limit, the constitutional act had from the very beginning envisaged introducing an operative fiscal management tool – expenditure ceilings – as an imperative component of responsible fiscal performance. However, the legislation on the public expenditure ceilings did not come into force until 11 years after the adoption of the constitutional act. With effect from 1 April 2022, the public expenditure ceilings became a key budgetary tool to achieve long-term sustainability of public finances, but they were only valid until 31 July 2024 in this form.

In the two years of their effectiveness, the rule has not been effectively applied and expenditure ceilings have not been bindingly used as the main instrument to ensure long-term sustainability. Even though approved by the parliament, the public expenditure ceilings for 2023 were not reflected in the approved state budget due to an exemption applied in connection with the European rules of the Stability and Growth Pact[20]. Subsequently, the approved general government budget for the years 2024 to 2026 was not prepared in compliance with the applicable expenditure ceilings[21], in violation of the law.

Instead of bringing the budget into compliance with the expenditure ceilings in force, the government approved an amendment to the Act on the General Government Budgetary Rules which fully linked the public expenditure ceilings to the revised EU rules under the Stability and Growth Pact with effect from 1 August 2024[22]. Public expenditure ceilings are now calculated by the Ministry of Finance on the basis of assumptions made by the European Commission.

According to the CBR, the adopted changes to the functioning of the expenditure ceilings are likely to be inconsistent with the concept of securing the long-term fiscal sustainability of the Slovak Republic as enshrined in Article 55a of the Slovak Constitution and in the constitutional Fiscal Responsibility Act. This represents a significant weakening of the existing regulatory framework because the public expenditure ceilings linked to the European rules do not sufficiently[23] reflect on the need to achieve long-term stability over the 50-year horizon.

This change in the functioning of the ceilings may slow down or even postpone the permanent recovery of public finances. The new rule on public expenditure ceilings does not require any consolidation effort to be made in 2024, and may even be met if the long-term sustainability of public finances deteriorates. The consolidation of public finances should start from 2025, and its strictness will also depend on whether the European Commission allows that the consolidation effort be spread over more than four years. According to the CBR, the new ceilings may not be functional and flexible enough. They will also involve a lengthy corrective process in the event of non-compliance, will be less circumvention-proof and more rigid in times of crisis.

Specific provisions for local governments

The rules applicable to the local government sector aim to separate the responsibility for the solvency of local governments from the state, to ensure that their new tasks are financed by the state and to prevent excessive indebtedness on the part of local governments. For these reasons, the following three areas are evaluated: 1/ whether the state has not provided funds to ensure local government solvency; 2/ whether the state has devolved new tasks and competencies to local government without providing adequate financial coverage, and 3/ the size of the local government debt.

- The CBR notes that the state has not provided funding to ensure the solvency of local government. In 2023, the government did not provide any new loans to local governments but released them from loans granted in 2020[24], temporarily improving their fiscal performance[25]. The existing rules on the provision of non-repayable financial assistance from the state’s financial assets need to be amended in order to preclude the selective favouring of local governments and to prevent their future insolvency.

- According to the available information, no new tasks were assigned to the local government sector in 2023 which would have required funding from the state[26]. However, the local government sector continues to face the negative effects of a major intervention in shared tax revenues (an increase in the tax bonus for children), the impact of which was not sufficiently assessed in advance by the government and parliament. The obligation to ensure adequate financial coverage under the constitutional act does not apply to changes in the existing local government competences that have no significant financial impacts. There are mechanisms in place through which local governments can raise funds in other ways (e.g., through tax hikes[27] or by shifting costs on users of services)[28]. Not using these mechanisms may indicate that funding problems are less urgent.

Any changes concerning the financing of local government must always be subject to a standard consultation procedure in accordance with the principles of transparency and effectiveness. It is also necessary to ensure that the impact of measures is consistently respected and monitored so that the central government authorities do not impose additional burdens on local government budgets without identifying them in the impact clauses, and at the same time to prevent any transfer of new tasks (whether in the exercise of original or delegated local government powers) to local government without adequate financial coverage.

- Administrative proceedings on the imposition of fines for 2022 on local governments with excessive debt[29] were closed. While all self-governing regions ended up with debts below the prescribed limit, the fines were imposed on three of the 34 initially identified municipalities after legislative exemptions had been considered and reported values cross-checked. There are currently 27 municipalities at risk of fine for 2023; the values they reported are now under review. Further 38 municipalities were contacted because they had not submitted the required financial reports. In 2023 too, the debts of all self-governing regions stood below the statutory limit. The Ministry of Finance assessed the compliance with the local government debt rule, with the possibility to impose a fine, for the first time for 2015, but not a single evaluation has been disclosed so far. The CBR recommends that the Ministry of Finance discloses[30] all information related to reviewing the size of local government debts, and imposing the fines, in a transparent manner.

Fiscal transparency rules

The fiscal transparency rules defined by the constitutional act were almost fully complied with. Macroeconomic and tax revenue forecasts were approved by competent independent committees and published within the deadlines specified in the constitutional act. The 2024-2026 general government budget contained all the data required by law, except for the information about a majority of companies with capital participation of the Ministry of Health of the Slovak Republic (healthcare facilities and Všeobecná zdravotná poisťovňa health insurer). The summary annual report for 2022 contained all the data required by law.

In addition to the requirements defined by law, the CBR also assesses the budget transparency in terms of comprehensibility and quality of the information contained in the assessed documents, consistent application of the ESA2010 methodology, and the measure of parliament’s control over the approval and fulfilment of the budget. These areas were also the focus of the CBR’s recommendations in its August 2023 report, but apart from a slight improvement in the comparability of the budget with reported data and the planned refinement of the quantification of net worth, no progress has been made in these areas. On the contrary, transparency has actually decreased as a result of the applicated use of the ESA2010 methodology and a move away from compiling budget expenditures on the basis of no-policy-change scenarios.

According to the CBR, the main persisting issues, the amendment of which could lead to further qualitative improvements in fiscal transparency and the overall budgetary process, include:

- The general government budget was not prepared in compliance with the budgetary objectives for the years of 2024 to 2026. In 2024, the budgetary objective set by the government was fulfilled by accounting for part of the emergency energy support measures financed from EU funds, which was inconsistent with the ESA2010 principles given the timing of such emergency support in 2023. In addition, the budget lacked specific consolidation measures for the next two years (in the amount of 1.1% and 1.6% of GDP, respectively).

- The CBR has repeatedly noted that the existing legislative framework governing the budget approval procedure in the parliament does not fit the scope and content of the documents that are being approved. Approving a cash-based (only) state budget by the parliament for the next year is based on a historical tradition, but this is no longer sufficient to capture the key monitored parameters of public finances and all changes in public finances in accordance with ESA2010 and the best international practice.

- The expenditure side of the budget should be based more on a no-policy-change (NPC) scenario for the next three years, as required in the past under the Act on General Government Budgetary Rules[31]. In the previous years, this approach was used only for the budgeting of expenditures of health insurance companies, which allowed a transparent assessment of the basic assumptions used in the preparation of the health sector budget, including the impacts of the measures included. The general government budget for 2024-2026 did not include such information even for expenditures in the healthcare sector[32].

- Better information should be provided for state-owned enterprises. A brief commentary on expected economic results of individual enterprises could enable better assessing any potential risks arising from the performance of enterprises owned by the state directly or through MH Manažment, a.s.

- The information value of the net worth indicator could be enhanced by the valuation of net worth components not yet quantified, which the Ministry of Finance is currently working on[33]. A broader analysis of the impact of government measures on the net worth will require the adoption of appropriate technical arrangements for the collection of data and the definition of methodology (in collaboration with the CBR) for linking the net worth change to the budget balance.